Looks like the press has picked up on what we’ve been talking about. This article below appeared on Malaysiakini, December 28, 2012.

————————————————————————————————-

As logging trucks zoom pass the Orang Asli village of Kampung Parik, the charred bamboos by the dusty mud road serve as a reminder of the struggle to preserve what is left of residents’ forest and way of life.

Awi Along, 41, (right) recalled the day when he and his Temiar kin said “enough” and mounted a blockade on one of the access roads outside this village against logging trucks.

Awi Along, 41, (right) recalled the day when he and his Temiar kin said “enough” and mounted a blockade on one of the access roads outside this village against logging trucks.

“The police dismantled the bamboo barrier and set fire to it. After that, they threw most of what remained into the river,” Awi recalled of the short-lived blockade of Jan 28 when 13 people were arrested.

Kampung Parik is among several Orang Asli villages spread along the Nenggiri River within the Kuala Betis regroupment scheme in Gua Musang, Kelantan, located on the outermost cluster of similar settlements, a mere 30-minute ride away from Kuala Betis town.

Not more than an hour in four wheel drive down the road from the former blockade site lies ancient Gua Cha, a neolithic settlement which the local Orang Asli proudly call the site of their forefathers.

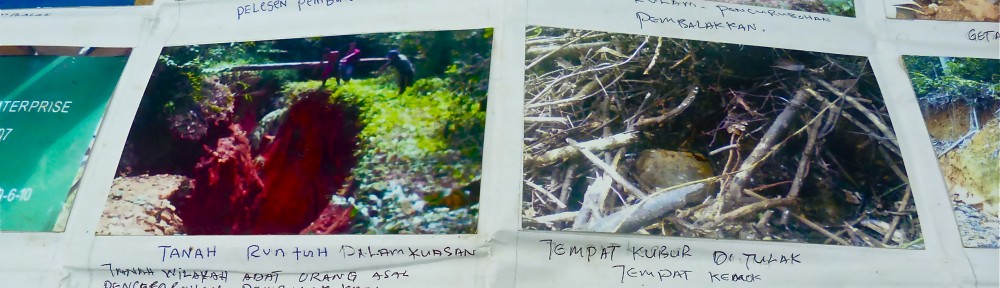

However, the path to the ancient cave saw what was once a landscape of majestic green now replaced by kilometres of rusty red barren hills littered with wood debris and dead trees.

Jelak Anas, 30, (right) from the nearby village of Kampung Depak, remembered how he had led a contented life by living off the forest until two years ago when bulldozers and terraces carved into the hills for a plantation put paid to that idyllic way.

Jelak Anas, 30, (right) from the nearby village of Kampung Depak, remembered how he had led a contented life by living off the forest until two years ago when bulldozers and terraces carved into the hills for a plantation put paid to that idyllic way.

“Five or six of us would enter the forest for a week or two and if we were lucky enough to find fragrant wood, we could sell them for up to RM5,000 at the town and share the money among ourselves but now nothing is left”, he said.

A short way down the road, thousands of bagged rubber tree saplings line the hill side, waiting to take their place on the terraces in yet another plantation within the Orang Asli domain.

This was a familiar sight for the more than 130 Orang Asli villages here that run deeper inwards up to the borders of neighbouring Perak and Pahang, boasting a population of over 10,000, majority from the Temiar tribe and the minority tribes of Menrik, Jahai and Batek.

The plantation is in the PAS-led state government’s Ladang Rakyat programme.

Aimed at alleviating poverty, the project grants participants monthly dividends of RM200, drawn from profits earned by leasing lands to private companies for plantations.

However, only a handful of Orang Asli benefit from this project with the vast majority finding their source of sustenance being destroyed, said Jimi Ariffin, 30 (left).

However, only a handful of Orang Asli benefit from this project with the vast majority finding their source of sustenance being destroyed, said Jimi Ariffin, 30 (left).

“This is because many of the participants of Ladang Rakyat are outsiders or those who are well connected, only a few are Orang Asli,” he said.

‘Trading livelihood for cash’

Chung Yi Fan, a researcher with the Bar Council on Orang Asli rights in the region said logging has been a common sight here but intensified with the introduction of Ladang Rakyat which saw mass conversion of forest land for plantations since 2006.

“Certain Orang Asli do receive dividends but the selection of participants in Ladang Rakyat scheme seems very opaque, how one becomes a participants is not entirely clear, you fill up a form to become a participant but you many not necessary become one.

“Certain Orang Asli do receive dividends but the selection of participants in Ladang Rakyat scheme seems very opaque, how one becomes a participants is not entirely clear, you fill up a form to become a participant but you many not necessary become one.

“Furthermore, how do you expect the Orang Asli to give up their native territory on which they rely for their subsistence and trade it for only RM200 cash a month,” he said.

The Auditor-General’s Report 2012 had criticised the Ladang Rakyat project, covering an area of 76,780 acres, with 41,472 acres in Gua Musang, as unsatisfactory and noted the local Orang Asli community’s concerns of encroachment into their traditional lands.

Kelantan Menteri Besar Nik Abdul Abdul Aziz Nik Mat had previously described dissent against the Ladang Rakyat as being masterminded by outsiders and had declared that until titles were issued, any land belonged to the state government.

This is aggravated by National Forestry Act 1984 which allows the clearing of forest reserves for planting rubber trees as long as they are capable of producing timber, said environmental and forestry researcher Lim Teck Wyn.

Dual purpose rubber forests

This comes in the form of Latex Timber Clone (LTC) which is a commercial rubber tree able to grow quickly and later provide timber.

“Certainly when people see rubber plantations, they would not normally think that it is a forest – that this kind of activity would be going on in a permanent forest reserve.

“The Orang Asli gather rattan, bamboo and other non-timber forest produce in these forest reserve, if you turn a natural forest into rubber plantation, then it wouldn’t contain many of the resources or wildlife the Orang Asli have been given right to harvest,” he said.

“The Orang Asli gather rattan, bamboo and other non-timber forest produce in these forest reserve, if you turn a natural forest into rubber plantation, then it wouldn’t contain many of the resources or wildlife the Orang Asli have been given right to harvest,” he said.

Lim, who is also Malaysian Nature Society committee member, estimated that close to 200,000 hectares of LTC will soon replace Kelantan’s natural forest.

While, having contributed to the Orang Asli ‘s shrinking source for subsistence needs, these commercial activities have also aggravated the deterioration of their quality of life, as Kampung Angkek, another village within the Kuala Betis regroupment scheme stands as testimony.

At first glance, this village which was the second blockade site, still enjoys the luxury of substantial greenery surroundings as logging here is done selectively and at some distance from the village.

At first glance, this village which was the second blockade site, still enjoys the luxury of substantial greenery surroundings as logging here is done selectively and at some distance from the village.

However, landslides caused by the logging had damaged the village’s gravity feed from a water catchment located approximately an hour’s ride uphill by four wheel drive, depriving the village of its traditional water supply.

“The landslides buried our water catchment, we have looked for a new catchment, but we couldn’t find a new one,” said Kampung Anggek village chief Damak Angah, adding that they now rely on the nearby river for water.

While the state government recognised lands around the immediate vicinity of the Orang Asli villages as rightfully theirs, Damak explained failure to consider the wider area by giving them out to private companies for commercial activities had adversely impacted the village.

While the state government recognised lands around the immediate vicinity of the Orang Asli villages as rightfully theirs, Damak explained failure to consider the wider area by giving them out to private companies for commercial activities had adversely impacted the village.

“We have no choice but to use water from the nearby river which looks like teh tarik, we don’t know what pesticides or chemicals flow into the river from the oil palm plantations nearby lamented Angah Anjang, adding that the logging had also made rivers down stream muddy.

‘Window-dressing projects’

On the federal government’s front, under the auspices of Jakoa, the village here is equipped with water tanks and pumps, but no water reaches the village.

This village, and like many others in Gua Musang are equipped with infrastructure constructed under various federal projects for the Orang Asli community, but many sit idle after completion.

This village, and like many others in Gua Musang are equipped with infrastructure constructed under various federal projects for the Orang Asli community, but many sit idle after completion.

Incidences of villages equipped with solar panels but without power due to worn out batteries and water treatment plants without water were not uncommon in neighbouring settlements.

“The equipment are just for show,” said Angah.

When contacted on this, Kelantan and Terengganu Jakoa director Faridah Mat declined to comment, asking that a written question be directed to the department. It has yet to respond to Malaysiakini’s facsimile text.

Over at Kampung Kinjing, yet another village within Kuala Betis regroupment scheme, too, faces a similar problem.

As night fell, the children huddled together in darkness around a small fire to keep warm. Utility poles stood outside this village, but there was no electricity.

“We’ve written several letters to complain, but it’s still the same, it has been like this for more than 20 years,” said Awer Awi, who has lived here since he was a child for the past 24 years.

“We don’t have running water here, so we need to rely on the river but the Kelaik River is red in colour,” said Angah Pandak (left), 55, pointing to the black and cracked skin on his leg, he claimed that the water was causing sickness among the local population.

“We don’t have running water here, so we need to rely on the river but the Kelaik River is red in colour,” said Angah Pandak (left), 55, pointing to the black and cracked skin on his leg, he claimed that the water was causing sickness among the local population. As the villagers surveyed the site which they claim is the source of their miseries, the factory’ manager, wishing to be known only as Tan and a group of men approached them.

As the villagers surveyed the site which they claim is the source of their miseries, the factory’ manager, wishing to be known only as Tan and a group of men approached them. This only happens during the rainy season because the rain water washes the soil into the river, it is not our water, our water is stored in our ponds and reused,” said its manager Julice Chu.

This only happens during the rainy season because the rain water washes the soil into the river, it is not our water, our water is stored in our ponds and reused,” said its manager Julice Chu. “We have also offered the locals work but they are not keen to take them up,” she said.

“We have also offered the locals work but they are not keen to take them up,” she said. “The reduction is probably because a portion of the iron was deposited along the riverbed but if there is heavy rain, it is possible that the iron level down stream will be much higher,” he said.

“The reduction is probably because a portion of the iron was deposited along the riverbed but if there is heavy rain, it is possible that the iron level down stream will be much higher,” he said.

Awi Along, 41, (right) recalled the day when he and his Temiar kin said “enough” and mounted a

Awi Along, 41, (right) recalled the day when he and his Temiar kin said “enough” and mounted a  Jelak Anas, 30, (right) from the nearby village of Kampung Depak, remembered how he had led a contented life by living off the forest until two years ago when bulldozers and terraces carved into the hills for a plantation put paid to that idyllic way.

Jelak Anas, 30, (right) from the nearby village of Kampung Depak, remembered how he had led a contented life by living off the forest until two years ago when bulldozers and terraces carved into the hills for a plantation put paid to that idyllic way. However, only a handful of Orang Asli benefit from this project with the vast majority finding their source of sustenance being destroyed, said Jimi Ariffin, 30 (left).

However, only a handful of Orang Asli benefit from this project with the vast majority finding their source of sustenance being destroyed, said Jimi Ariffin, 30 (left). “Certain Orang Asli do receive dividends but the selection of participants in Ladang Rakyat scheme seems very opaque, how one becomes a participants is not entirely clear, you fill up a form to become a participant but you many not necessary become one.

“Certain Orang Asli do receive dividends but the selection of participants in Ladang Rakyat scheme seems very opaque, how one becomes a participants is not entirely clear, you fill up a form to become a participant but you many not necessary become one. “The Orang Asli gather rattan, bamboo and other non-timber forest produce in these forest reserve, if you turn a natural forest into rubber plantation, then it wouldn’t contain many of the resources or wildlife the Orang Asli have been given right to harvest,” he said.

“The Orang Asli gather rattan, bamboo and other non-timber forest produce in these forest reserve, if you turn a natural forest into rubber plantation, then it wouldn’t contain many of the resources or wildlife the Orang Asli have been given right to harvest,” he said. At first glance, this village which was the second blockade site, still enjoys the luxury of substantial greenery surroundings as logging here is done selectively and at some distance from the village.

At first glance, this village which was the second blockade site, still enjoys the luxury of substantial greenery surroundings as logging here is done selectively and at some distance from the village. While the state government recognised lands around the immediate vicinity of the Orang Asli villages as rightfully theirs, Damak explained failure to consider the wider area by giving them out to private companies for commercial activities had adversely impacted the village.

While the state government recognised lands around the immediate vicinity of the Orang Asli villages as rightfully theirs, Damak explained failure to consider the wider area by giving them out to private companies for commercial activities had adversely impacted the village. This village, and like many others in Gua Musang are equipped with infrastructure constructed under various federal projects for the Orang Asli community, but many sit idle after completion.

This village, and like many others in Gua Musang are equipped with infrastructure constructed under various federal projects for the Orang Asli community, but many sit idle after completion.